By Samudra De Silva

From the shallow seagrass beds of the Indian Ocean, and vivid reefs of coral triangle to sandy coasts of the Eastern Pacific, seven different species of sea turtles swim through our ocean waters. As a highly migratory species, turtles periodically come ashore to nest, and spend the most of their lives in the ocean. For more than a hundred million years, sea turtles have played a crucial role in sustaining the balance of our marine ecosystems. They fortify productive coral reefs and transfer nutrients from the ocean to coastal dunes. Over the last two centuries, human activities have growingly challenged the survival of these ancient mariners.

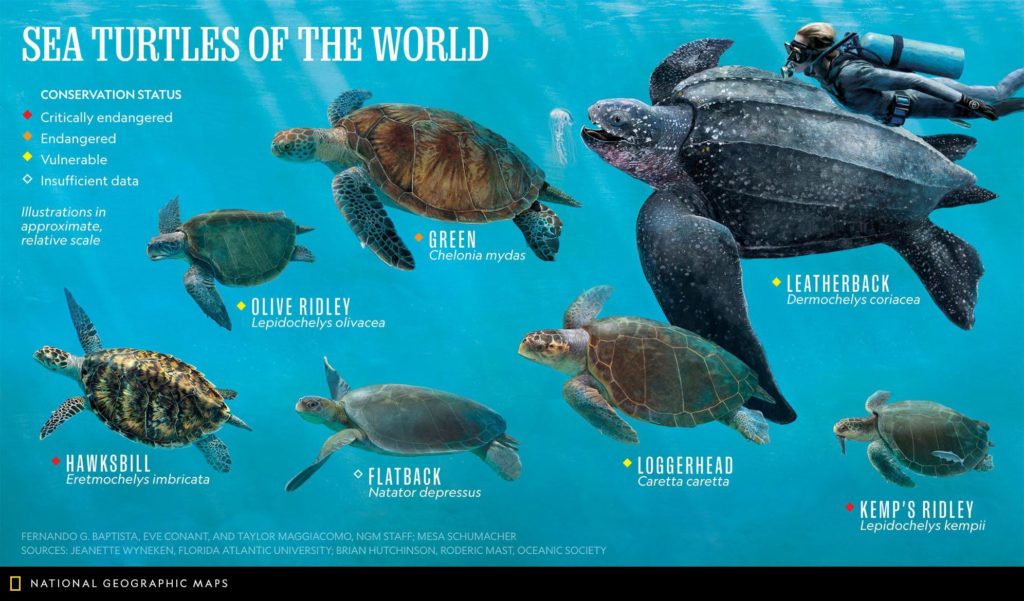

Today Sea turtles are being completely erased from some parts of the planet and pushed to the verge of extinction. Nearly all seven existing species of sea turtles are now classified as endangered, with three of them being critically endangered. But at the same time, sea turtles are one of the most loved and discussed among marine animals. There is hardly anybody who hate these graceful flippers. It is important to review how we knowingly or unknowingly have doomed their lives.

Sea turtles are victims of poaching and over exploitation. They have been slaughtered for human consumption and their meat, skin, and shells are traded as food, medicine, collectibles, and spiritual artifacts over the years in unsustainable levels. Turtle eggs are collected from nesting sites as food and for their alleged aphrodisiac effect. Hawksbill turtles are hunted for their unique gold and brown shells used in making jewelry and other collectibles. Many other sea turtle species are killed for their skin, which is sold as a raw material for leather accessories. A global assessment on illegal marine turtle exploitation, demonstrate that over 1.1 million sea turtles were exploited from 1990-2020 against existing laws prohibiting their use in 65 countries with over 44,000 turtles exploited annually over the past decade. Exploitation across the 30 years dominantly consisted of green (56%) and hawksbill (39%) turtles when identified by species. International trade of all species of sea turtles and their parts is prohibited under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), a global agreement among 173 governments to regulate or ban international trade in species under threat, yet illegal trafficking persists, especially in parts of Africa, Asia and the America.

Bycatch or the incidental capture by fishing gear is lethal to most sea turtles, especially endangered loggerhead turtles, greens turtles, and leatherback turtles. Worldwide, hundreds of thousands of sea turtles are caught up in shrimp trawl nets, gill nets, and on longline hooks every year. Since sea turtles need to reach the water surface to breathe, many drown once entangled in the nets or hooks. This threat is increasing alarmingly as fishing activity expands. However, some relatively inexpensive changes in fishing gear, such as using larger hooks from which sea turtles can escape, is observed to bring down the mortality rate. Turtle excluder devices (TEDs) could reduce sea turtle bycatch in nets as well.

Along with many other species, sea turtles face habitat loss. Feeding grounds of turtles such as sea grass beds and coral reefs are continually deteriorated by natural and human activities including sedimentation, nutrient run off from agriculture, and beach restoration through sand filling. Human development projects such as beach nourishment, parks, rock jetties, and buildings on beaches can reduce the amount and quality of available nesting sites for sea turtles. Human generated light is a serious threat to newly hatched sea turtles. Hatchlings are naturally attracted to light as the brightest area on a natural beach is the horizon over the ocean. Bright light emitted from streetlights and building on beaches causes hatchlings to become disoriented, crawling towards the light on the land and away from the water. Some beaches with high turtle nesting density have lost thousands of hatchlings due to impact of artificial light. There are recorded cases where large number of hatchlings were run over by vehicles after disorienting and crawling onto roadway. Noise and human activity on the beach also may cause females turtles to return to the sea instead of nesting.

Pollution, both chemical and physical, has become fatal. Trash in ocean and along coastlines, lowers the quality of their feeding grounds and nesting sites. Turtles seem to confuse solo drifting debris with their diet, and many turtles are dying from intestinal blockage due to ingestion of balloons and plastic bags which resemble their gelatinous translucent prey (jelly fish). A recent study shows that loggerheads ate plastic 17% of the time they encountered it, mistaking it for jellyfish. It escalated to 62% for green turtles, likely on the lookout for algae. The chemicals ingested from the plastic can leach into their eggs and affect offspring. A high level of phthalates has been measured in Leatherback turtle eggs’ yolks, which can disrupt endocrine activity in hatchlings. In 2015, an Olive Ridley sea turtle was found with a plastic drinking straw lodged inside its nostrils. Sharp objects found in marine debris can cause both internal and external injuries in sea turtles, which turns lethal. Sea turtles are vulnerable to oil spills because of the oil’s tendency to linger on the water’s surface, and affect them at all stages of their life cycle.

Climate change which is a long term and inevitable outcome of pollution has an impact on turtle nesting sites, as alterations in sand temperatures of the nest which determines the sex of hatchlings. Unusually warm temperatures are disrupting the normal ratios, biasing towards females resulting in fewer male hatchlings, or even preventing any of the eggs from hatching. The right balance between sexes is a determining factor for the continued procreation of this critically endangered species. Warmer sea surface temperatures can also lead to the loss of important foraging grounds for sea turtles, while increasingly severe storms and rising sea levels can destroy nests and erode beaches, making safe nesting sites severely scarce. Altering ocean currents, which are the highways that sea turtles use for migration, cause them to possibly have to shift their range and nesting time.

Unregulated leisure activities organized by travel and tourism businesses, such as “swim with sea turtles” followed by tourists feeding the animals, are exposing them to health risks. Too much of human intervention can disturb beaching turtles and scare them away. Often such activities are conducted with primitive knowledge on the behavior of these sensitive marine creatures, and only focuses on the financial gain. There are recorded cases where captive turtles are used for such businesses. Not only is it unethical and illegal, keeping away a mature animal that could reproduce, and stopping it from contributing to the genetic pool is ill- fated for the survival of a species, specially an endangered one.

Mismanaged conservation efforts such as sea turtle hatcheries seem to impact sea turtles in an opposing way than what they are planned for – which is to protect, rehabilitate and release back into the wild. Usually the turtle eggs are collected from the beach so as to avoid the risk of poachers and predators. Once the turtles hatch, they are monitored and released in to the ocean. Research demonstrates that relocating eggs alter hatchling gender ratios as well as the hatchling rate, possibly due to unusually warmer temperatures and overcrowding. In natural circumstances, the hatchlings are supposed to enter sea as soon as they hatch. Unfortunately, commercial turtle hatcheries act as tourist bait until an entrance fee is paid to release the sea turtles to the ocean, and they are kept in cement tanks until then. The cement tanks cannot simply replicate a sea environment in terms of salinity and the space that the sea turtles are habituated to, as highly migratory animals. Overpopulated, unhygienic and poorly maintained tanks caused spread of diseases among captive hatchlings, and allowing tourists to touch them further increases the risk of contamination and diseases. Hatchlings lose their stored energy by swimming continually in tanks at its critical stage of development, downgrading their survival rate when they eventually swim out to the deep ocean. Rehabilitation through hatcheries also interfere with the unique imprinting mechanism of sea turtles which naturally guide them to return to their natal beach to lay their own eggs someday.

Such human generated threats to sea turtles are escalating along with the rising human populations around the world. In-situ conservation, strengthening protected areas around nesting beaches, raising public awareness on the behavior of sea turtles, promoting ecotourism, lobbying for turtle friendly fishing practices, and minimizing of plastic debris and chemical contaminants which end up in the sea, will be helpful to ensure the tomorrow of those unique and graceful mariners who share the planet with us.

Header Image: NPS Photo via US National Park Service

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.